Leo Lionni wrote and illustrated more than forty children’s books in his lifetime, but the one which is the most meaningful to me might be his most famous: Frederick, the story of a little field mouse who keeps his family warm in the middle of a cold winter, by reciting poetry that is so beautiful and so evocative of sunnier seasons. A close second to Frederick might be Swimmy, the story of a little black fish who is not like the other red fish in the nearby schools, who teaches the other fish around him to be brave, so that they might explore the wonders of the ocean together.

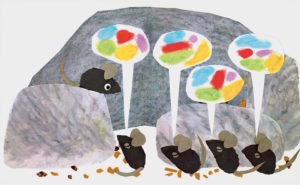

Lionni, who was a painter and sculptor, produced some of the most beautiful illustrations I’ve ever seen. His characters are brought to life via paper cutouts (including cutouts of painted paper), as well as inventive manipulations of paint, including stamping and pressing. The results are ethereal and soft—his mice are textured with the fuzzy edges of fine, handmade paper, and his seaweed forests look like lace. I would be happy staring at his paintings all day long.

Lionni, who was a painter and sculptor, produced some of the most beautiful illustrations I’ve ever seen. His characters are brought to life via paper cutouts (including cutouts of painted paper), as well as inventive manipulations of paint, including stamping and pressing. The results are ethereal and soft—his mice are textured with the fuzzy edges of fine, handmade paper, and his seaweed forests look like lace. I would be happy staring at his paintings all day long.

Born in 1910 in Holland to Dutch parents but raised in Italy until he emigrated to the United States as an adult in 1939, Lionni did not begin writing children’s books until later in his life. As the story goes, he had been attempting to entertain his young grandchildren on a long train ride, and ripped circles out of a nearby magazine to use to tell them a story—inspiring his first picture book, Little Blue and Little Yellow, which was published in 1959. But before this, Lionni’s career was richly varied. He had taught himself to draw as a child, by copying the works of the Great Masters in Amsterdam museums, but formally studied economics, receiving a PhD from the University of Genoa in 1935. A respected avant-garde painter in Italy, he pursued advertising when he arrived in Philadelphia in 1939. In 1948, he became the art director of Fortune Magazine, a position he held for twelve years. But during these years, he also did work as a designer for private clients, illustrating graphics for clients like MoMA and Olivetti. In 1960, he returned to Italy, buying a home in Tuscany to pursue children’s book-writing, full-time. He lived and worked there until his death in 1999 at the age of eighty-nine. He was a four-time recipient of the Caldecott Honor, an award for excellence in picture book illustration.

The first Leo Lionni book I read was A Color of His Own, a story of a chameleon who is unhappy that his skin naturally  imitates his surroundings, instead of providing him with his own, unique tone. I was little, living in Queens, New York, where I was often cared for during the day by my grandparents, Croatian immigrants. My Croatian grandfather—my Nono—who had long before taught himself to read English from newspapers after he immigrated to New York City in 1950, would read with me. I was little—two years old or so, which I know because in these memories, my mother is not pregnant with my younger sister yet—but I would memorize the words from listening to him speak them. He was worried that I wouldn’t learn how to read if I kept doing this, and he kept pausing, after I’d finish his sentences, to encourage me to look at the letters on the page while he spoke. I know we read A Color of His Own together—I remember sitting on the floor in their house in Flushing, holding it. In the story, the chameleon learns to appreciate his difference, when he meets another chameleon just like him, and learns that his ability to reproduce the colors around him allows him to wear so many beautiful colors and patterns. It’s not so simple as an Ugly Duckling story which shifts its main character from social nonconformity to social conformity to communicate perspective shifts regarding appreciation and belonging—but A Color of His Own is also about being taught about your own abilities and skills from someone who is older and wiser, in them. Our chameleon hero does not know what he can do, until he meets someone who can show him how.

imitates his surroundings, instead of providing him with his own, unique tone. I was little, living in Queens, New York, where I was often cared for during the day by my grandparents, Croatian immigrants. My Croatian grandfather—my Nono—who had long before taught himself to read English from newspapers after he immigrated to New York City in 1950, would read with me. I was little—two years old or so, which I know because in these memories, my mother is not pregnant with my younger sister yet—but I would memorize the words from listening to him speak them. He was worried that I wouldn’t learn how to read if I kept doing this, and he kept pausing, after I’d finish his sentences, to encourage me to look at the letters on the page while he spoke. I know we read A Color of His Own together—I remember sitting on the floor in their house in Flushing, holding it. In the story, the chameleon learns to appreciate his difference, when he meets another chameleon just like him, and learns that his ability to reproduce the colors around him allows him to wear so many beautiful colors and patterns. It’s not so simple as an Ugly Duckling story which shifts its main character from social nonconformity to social conformity to communicate perspective shifts regarding appreciation and belonging—but A Color of His Own is also about being taught about your own abilities and skills from someone who is older and wiser, in them. Our chameleon hero does not know what he can do, until he meets someone who can show him how.

Many of Leo Lionni’s stories are about community, in the truest sense. They are not about outsiders who struggle to fit in or who are ostracized for difference. They are about individuals within the community who bring new, useful qualities to the group. The little black fish in Swimmy or the mouse-bard Frederick in Frederick are marked as different, but they are not shunned because of it. This way, there is no conflict in the Leo Lionni stories, no representations of exceptionalism or being “misunderstood.” Swimmy, in Swimmy, is the only little black fish in a sea of red fish, and he winds up escaping coincidentally when a tuna eats all the red fish in the area. He is afraid, but as he swims through the ocean alone, he is mesmerized by the beauty of the new underwater world. He meets a school of red fish just like his family, and he tries to convince them to explore with him. But they won’t—afraid that a large fish will gobble them up. So Swimmy comes up with a plan: he teaches all the fish how to swim together, so that they can take the form of a giant fish.

And they roam through the sea together, scaring away all the predators, finally able to experience the visual wonders of the ocean. In Swimmy, the moral is deeper than that there is strength in numbers. The community is simply freer, happier, safer, and able to enjoy their lives, when everyone works together, looking out for one another. Swimmy happily takes his place as the “eye” of their giant fish creation—finding his ideal spot in the collective, but participating just the same. It’s not a coincidence that Swimmy is the eye, since he is the visionary behind this all. (I remember, so vividly, my father reading this part aloud to me, when I was small). Similar is the story in Frederick—instead of gathering grain like his family, Frederick spends the last days before winter trying to remember the beauty and warmth of the world around him, so that he might use it to entertain and aid his family when the nights grow cold and the food runs out.

The fish and the mice accept Swimmy and Frederick even though they are different, and when the time comes, Swimmy and Frederick figure out how to use their differences to help the community. There is no isolation in Lionni’s novels—no alienation or estrangement or even the idea that those who are different are secretly better than everybody else. This is good, because these themes can be insidious. In Lionni’s books, there is no competition, no jealousy, no territoriality. There are, however, attempts to make connections despite difference. I think especially of Alexander and the Wind-Up Mouse, about a real mouse and a toy mouse who become friends, or the two circles in Little Blue and Little Yellow, who, when they come together, make green.

For all that they are about transcendence, Lionni’s books are highly existential. His heroes are often in possession of some degree of knowledge deeper than those they know, and they struggle to find or make meaning amid the monotonous routines which surround them. In Lionni’s oeuvre, this is mediated through art. His protagonists are often all artists—motivated by discovery and innovation, transfixed by beauty, invested in honing their skills, committed to evoking the majesty they see, and, above all, determined to bring it to other people. Art, for Lionni, is always public, and always free. It exists to transform the humdrum, but it also exists to celebrate beauty which already exists in the world. And it’s for the people. The artist is not elite, in Lionni’s books, but a vessel, an instrument for the transmission of beauty.

Art literally saves the communities it is brought to, and this, in a way, is how Lionni’s books mediate the existential crises that haunt our artists; Swimmy’s giant fish, which allows the school to actually travel through the spectacular world of the ocean, saves them from being eaten. Frederick’s poems about the seasons make the mice feel warm and fortified in their chilly cave, and allow them to preserve their strength to make it through the season. The little inchworm in Inch by Inch uses the pretense of his craft (perfectly measuring everything with each of his steps), to escape a nightingale who wants to eat him.

I loved, as a child, how these books represented storytelling and art-making as just as valuable as more “practical” skills. The world needs art, and everyone benefits from it, these books explained. Even while they do not understand the work he is doing, the field mice do not decry that Frederick is not pitching in, in the same manner that they are. Art is work, Moreover, it is valuable work. I also loved how these books champion sharing and solidarity, mentoring and friendship. In these books, it is critical that the citizen not hoard his resources, it is critical that the artist not hoard his vision, but it is also important that the person not hoard himself. In Lionni’s books, the connection between one another is the most important thing we have. And it is by reaching out, grasping hands, that we build a better, more beautiful world, one we can all enjoy.