We live in unreal times. I wake up in the middle of a global pandemic to watch a reality-TV president spout conspiracy theories while dystopian corporations enact new science fiction tech. In this chaos, I’ve found myself turning to escapist fiction. Stories that conjure a different, more peaceful and stable world. For me that’s been stories labeled “realism.”

Recently I escaped into James Salter’s masterful Last Night. Salter’s short stories are deeply moving and filled with gorgeous prose. Yet these stories of wealthy people having affairs and dinner parties are scrubbed of bitter partisan politics, foreign wars, and crumbling economics that have defined my own experience of American life, even though the book was published in Bush’s second term.

I’m not critiquing Salter, who is one of the most stunning prose writers in American literature. But it’s made me wonder about “realism.” Are Salter’s stories more real than, say, the stories of George Saunders which may include fantasy or SF elements yet more clearly evoke the daily news? Is “realism” a useful term in 2020? Was it ever?

*

Imagine a football field of fiction. The left endzone perfectly imitates reality. The right endzone fully invents a new one. Art, being imperfect, can never reach either goal. But perhaps the left five-yard line is dotted with the dirty realism of Raymond Carver or researched historical fiction like Wolf Hall while the other five-yard line has the fantastic imaginings of Star Wars or Lord of the Rings. Everything to the left of the 50-yard line is “realism” and everything to the right of it is “science fiction and fantasy.”

This is how many readers, authors, and even critics view the terrain of literature. (And, yes, sadly many view it as a competition where we must choose a side.) Literary discourse often devolves into squabbling over the failed “realism” of stylized novels like Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch and Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life or debates about whether magical realism is just fantasy for literary snobs.

Last year, an award-winning SFF author told me that non-realist literary authors like Karen Russell and Donald Barthelme were “actually science fiction and fantasy writers” while also mocking non-realist literary authors for “not even thinking through their worldbuilding.” The result is a big confused mess that leaves whole swaths of literature—fabulism, surrealism, hysterical realism, postmodernism, and so on—floating in the ether.

Realism is not a binary. It is at a minimum a spectrum. If you charted fictional realities on a football field, you’d find that work on the 45-yard “Realism” side is closer to the 45-yard “SFF” marker than it is to, say, Sally Rooney over the 8-yard line. But even a spectrum doesn’t accurately capture the vast ocean of fiction that takes our reality and heightens, stylizes, distorts, or warps it in different ways.

Take Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest. Wilde’s play is “realism” in the narrow sense of taking place in our world—gravity is the same, there are no dragons or vampires, etc.—yet the plot revolves around a series of intentionally absurd coincidences and the characters speak in polished bon mots. Wilde, who hated the trend toward realism, was certainly not attempting to recreate reality. But there’s little in common between Lady Bracknell and a Balrog.

On the other hand, where do we place a chillingly realistic yet reinvented version of our world like Philip Roth’s The Plot Against America, which imagines an alternate American history where fascism ascends during World War II? Once, someone passionately argued it was science fiction because of some rationale involving wormholes and the multiverse. Somehow, I doubt wormholes were what was on Roth’s mind. And I’ve yet to see anyone argue that Curtis Sittenfeld’s Rodham, which imagines an alternative history where Hillary never married Bill Clinton, is science fiction.

Lastly, think of Franz Kafka’s “The Judgement.” This story, like most of Kafka’s work, has no overt fantasy or SF elements. (“The Metamorphosis” is an outlier in this regard.) In “The Judgement,” a guy is in a house talking to his father about his engagement and business. But the tale has a dream logic and nightmarish atmosphere that is operating on a field far away from realism.

These examples—the aestheticism of Wilde, alternate histories of Roth and Sittenfeld, and Kafkaesque nightmares—are just three of countless ways reality can be skewed, distorted, or heightened. When we look at the scope of literature, very little of it fits neatly into the realist box.

*

A couple years ago I was teaching Ursula K. Le Guin’s “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” when a student complained that the whole thing was “too unrealistic.” On his desk, I saw a copy of A Game of Thrones.

At the time I found the comment, like the above tweet, funny. But in truth this student, like the SFF author who claims magical realists are “not even thinking through their worldbuilding,” was not entirely wrong. The fabulist parable of “Omelas” is not operating in the (relatively speaking) realistic mode of A Game of Thrones. Le Guin herself has argued that “serious science fiction is a mode of realism, not of fantasy.” Serious attempts to portray changes to reality have more in common with realism than they do with, say, fairy tales. The modes are similar.

Historically, “Realism” was a question of mode. The term was used to distinguish naturalistic works from forms like Romances (chivalric, not bodice-ripping) and Gothic novels. Those latter modes sometimes contained unreal elements like dragons or ghosts, but not necessarily. Mainly they differed in presenting a heightened reality with increased drama, humor, sentiment, grotesquerie, and so on.

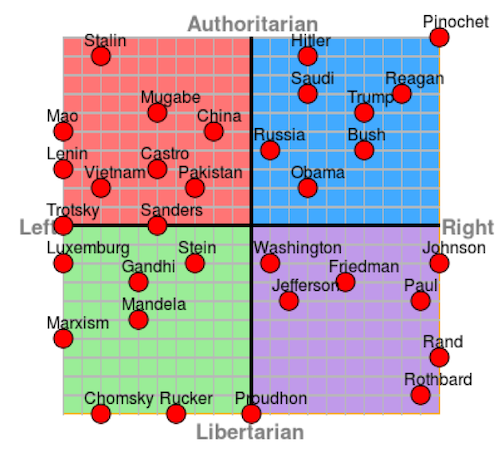

What would it look like to reject realism/SFF as a binary and to acknowledge mode? While making notes for this essay I thought of the political compass that frequently makes its way (often as memes) around the internet. The compass uses two axes to give us four broad quadrants to give us a somewhat more nuanced view of the ideological spectrum than a left/right binary:

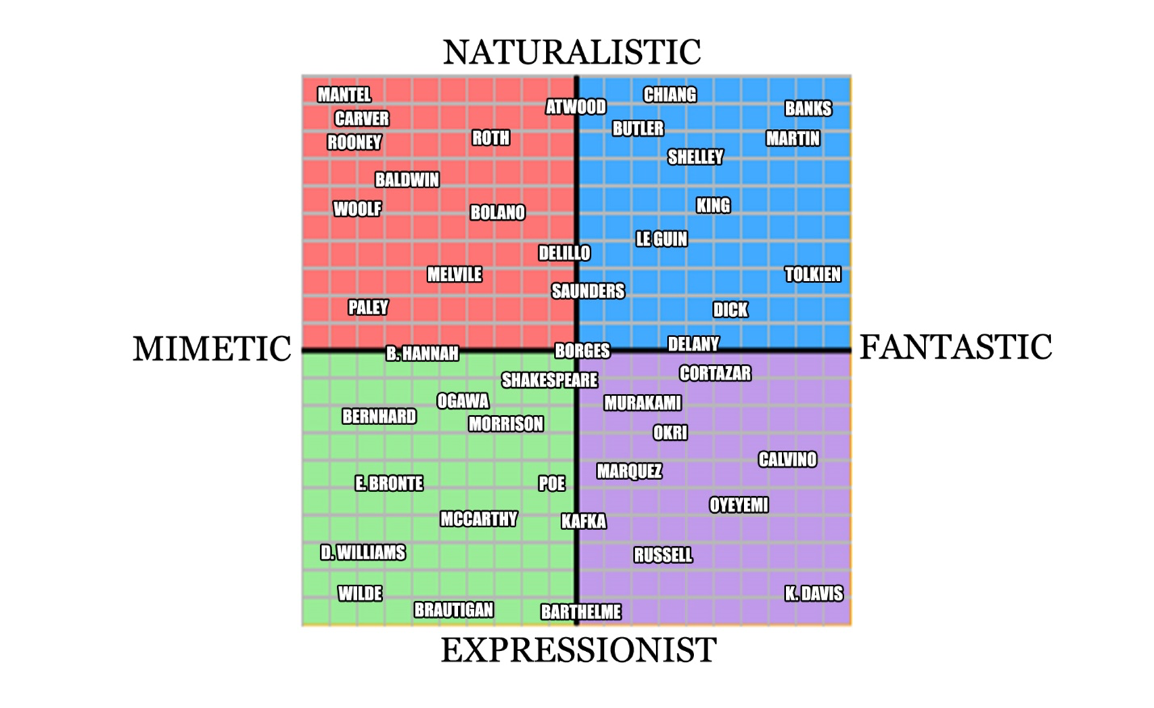

We could chart literature this way with two axes I’ll label the mimetic—fantastic and the naturalistic—expressionist. You might call these the world scale and the mode scale. The first axis is pretty obvious. To what degree does the fictional world follow the physical laws and actual history of our world? For the mode axis, it might be useful to think of visual art. In a naturalistic painting, the image attempts to look as it does through our eyes. In an expressionist painting the contents of the painting may be mundane, but the depiction is twisted and estranged.

October by Jules Bastien-Lepage (1878)

October by Jules Bastien-Lepage (1878)

The Scream by Edvard Munch (1893)

The Scream by Edvard Munch (1893)

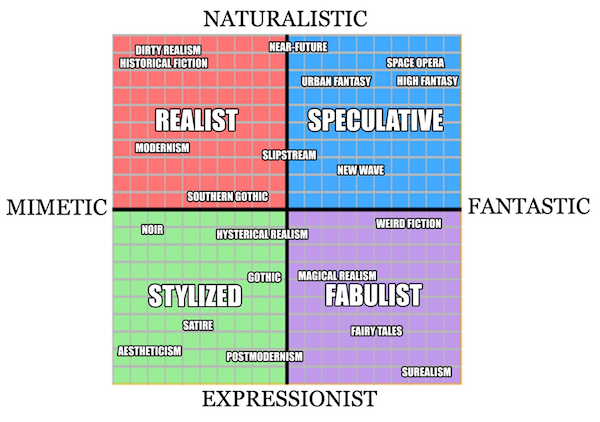

Graphing literature with a world axis and a mode axis gives us four quadrants that I’ll label Realist, Speculative, Fabulist, and Stylized. (Note: what I label “stylized” reality is not a claim that these books are written with more or less stylish prose.)

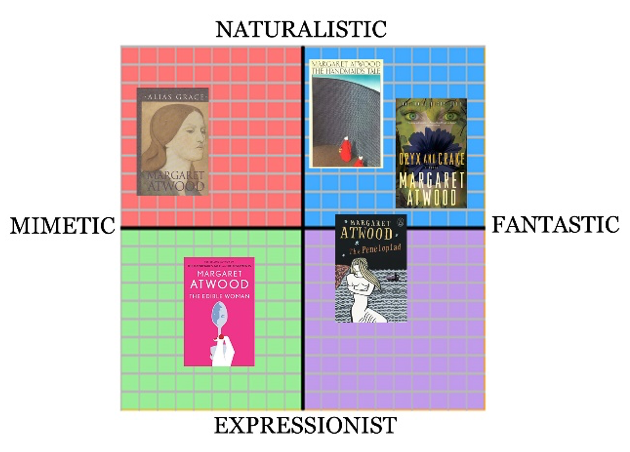

Some of the styles and subgenres are more locked-in than others. Surrealist authors are always in the lower right corner. However, some postmodernists like Barthelme and Coover fit in the lower middle while others might be more mimetic or more naturalistic. Similarly, before I try scattering some authors on this graph, a major caveat: few authors stay entirely in one area. Indeed some authors—Kazuo Ishiguro and Margaret Atwood, for example—move all over the map.

I want to stress here that this is a chart of fictional realities, which is only one part of fiction. Ishiguro has a consistent style and deploys similar themes whether he is writing realism (The Remains of the Day) or fabulism inspired by Arthurian legend (The Buried Giant). And two books on the same point of this chart might read wildly different in terms of the authors’ styles or structures—to say nothing of plot, story, and character. All placements are tentative and inexact. Authors roam. With that caveat, here’s an old college try:

I’m sure people can (and will—muting my Twitter notifications now) disagree about the exact placements, but I think this chart reveals a whole lot that the realism/SFF binary obscures. Expressionist and fantastic styles like magical realism use magic for poetic and symbolic effect that is in many ways closer to postmodernism than it is to, say, a high fantasy writer like Brandon Sanderson who says “magic works best for me when it aligns with scientific principles.”

On the other hand, one could make a strong argument that the immersive and (relatively) naturalistic worldbuilding of A Song of Ice and Fire has more in common with historical fiction like Wolf Hall and I, Claudius than it does with the surrealism of Leonora Carrington. Dreamy Gothic works like Wuthering Heights may be closer to Franz Kafka than they are to Raymond Carver, and so on.

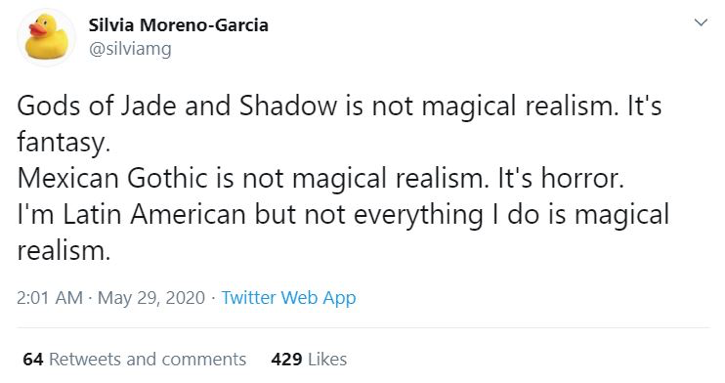

Decentering “realism” also reminds us that what we find “realistic” is more ideological than it is aesthetic. To declare Lorrie Moore is more real than Carmen Maria Machado or Raymond Carver more real than Toni Morrison is to privilege a certain experience of reality. It is not a coincidence that the work of straight white Americans is more likely to be called realism while authors from other cultures, backgrounds, and traditions are frequently all lumped together as “magical realism.”

In modern American literature, both the literary fiction world and the SFF world have a bias toward naturalistic modes. In the literary world, this means a bias toward the naturalistic realism of Carver types and autofiction. In the SFF world, this means a bias toward worldbuilding-focused works, “hard” over “soft” science fiction, and Sanderson-type “scientific” fantasy authors. But this bias is not eternal or global. It is recent and cultural.

For my tastes, there is no point on this chart that is better, more rigorous, more moving, or more relevant than any spot. Every single point on this chart has its own strengths and possibilities. The pleasures of fabulist literature are simply different from the pleasures of hard science fiction, just as the effects of noir are different than the effects of autofiction.

As authors, understanding where our stories chart helps us improve and sharpen the work. As critics, understanding the multiple directions that reality can be skewed might help avoid the still-far-too-common complaints about “unrealistic” elements of intentionally unreal works. Once we understand all that, perhaps we can do away with “realism” altogether.