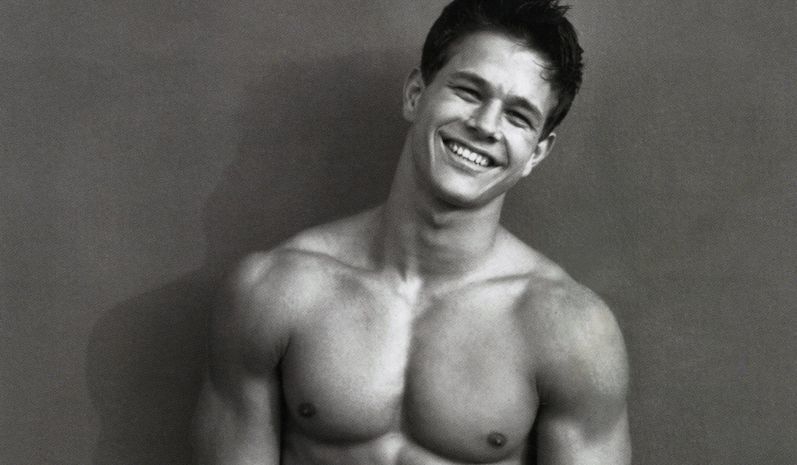

For me, it began in the men’s underwear section. It was there that I first saw them, that carved alabaster lot, a pantheon of idolized physiques. David Beckham, Freddie Ljungberg, Jamie Dornan, and—of course, the archetype—the classical Marky Mark. Long before the Greek antiquities room at the Met in New York, I had Macy’s at the Fashion Show shopping mall in Las Vegas. That gallery of bodies informed my sexual ideal, those aisles of men seemingly hewn from marble. Many pubescent gay boys go through this rite of passage, stealing glances at the packages on such packages, imprinting on men who’ve come from Olympus itself.

I would abscond to that PG-13 corner of Macy’s whenever my mother gave me money and time at the mall. After taking in a visual feast of chiseled bodies, I’d rearrange my erection and pick a package I could take home. Just as I once bought a studded belt and bracelet at Hot Topic to better resemble the classmate I was crushing on, I took those opportunities to buy what I hoped would make me desirable, would link me to other men.

The blinding whiteness of those underwear aisles was not lost on me. From the first Calvin Klein ad in 1982, featuring the Olympian Tom Hintnaus viewed from the bottom, to Mark Wahlberg in his Calvins in 1992, to David Beckham smoldering in repose for Emporio Armani in 2008—those campaigns and images were persuasive, even when they were diluted into less intentionally provocative images on packaging for Fruit of the Loom. They gave the impression that to be white and muscular were prerequisites to being sellable, worthy of being wanted. Here were two lessons bundled into one for queer little boys: what to desire and what to desire to become. As a young Filipino immigrant beginning to engage with American culture as practice, I didn’t question the messaging and bought into it instead. These ads didn’t just sell garments. They sold the very myth of American masculinity.

Here were two lessons bundled into one for queer little boys: what to desire and what to desire to become.

Underwear ads have been a site of this mythmaking for ages. Well before Calvin Klein, there were the decadent ads drawn by J. C. Leyendecker in the early twentieth century for men’s outfitters like Kuppenheimer, Cooper Underwear (now named Jockey). He drew his men not only as jocks (rugby boys and crew captains) or as dandies (dashing bachelors in white tie), but as both (squash players), always in contexts of WASPy affluence. What Leyendecker and Calvin Klein created was an image of the archetypal American man—one whose attractiveness was charged with classical ideas of masculinity and whiteness.

Recently, men’s underwear ads have featured more people of color. In the late 2000s, Calvin Klein enlisted Djimon Hounsou, a black model and actor from Benin, and Hidetoshi Nakata, a Japanese footballer, into their campaigns. These castings expanded the masculine ideal, but they still had their limits. Like their white counterparts, these idols still had carved abs and bulging biceps, as if sculpted by Michelangelo himself from bronze and brass, rather than the marble he saved for David. The lesson, then: desirability could be accessed through whiteness or sheer brawn, most easily through both.

Underwear ads alone don’t dictate the gay male obsession with whiteness and masculinity; various cultural phenomena also teach racism and internalized femmephobia. Still, the people behind such ads and images—very often queer men themselves (who do you think drew the swollen muscles on Hercules and Zeus in the Disney film?)—set the standards of male beauty. They then use those standards to sell their products to anyone who will listen, queer or otherwise, implying that their products provide an avenue to that beauty. That’s how advertising works. And I bought Calvin Klein capitalized on my need for validation, for mythic signs of virility. Whenever I met up with Christian, or Gareth, or Adam, or any of my nameless men, I always made sure to wear my Calvins, even though they couldn’t make me look like Marky Mark or David.

I didn’t see myself as anything but a twink, at the ages of twenty and twenty-one, with only the nubile charms of a Filipino boy to leverage in uber-competitive New York. While some men took this bait, more common were those who disclaimed in their profiles, “no fats, no femmes, no Asians.” (Or “no spice, no rice.”) Sometimes, men who wrote such slurs fucked me anyway, reminding me how racists might make exceptions in the name of conquest. Even in my Calvins, it was clear I wasn’t one of them, the men who held me at arm’s length even when they were inside me. But I took such evenings as concessions and kept on with the chase. Like them, I was a product of conditioning, taught to think only these white muscular men were desirable.

Christian appealed because he knew all this, understood the theory that animated my anxieties. Over dinner, we’d skewer the masc4masc habits of our fellow queens who idolized stereotypes of hypermasculinity, who couldn’t intuit, as we did, the oppressive systems at work—the code in the matrix, as it were. We thought highly of ourselves, we admitted, and yet maintained our ambitious gym routines, stuck on that hamster wheel.

When he conceded that he loved French cooking and butter too much to possess the coveted six-pack abs, I felt camaraderie in that admission, though he was still white—like them, unlike me. But I focused on how we reflected each other instead. We fancied ourselves aesthetes, learned in the ways of epistemology and camp, heirs to a more cerebral and sibilant tradition, one that celebrated reading queerly.

Christian taught me about the homoeroticism in Leyendecker’s art—the men’s macho suiting, homosocial schemas, and dextrous glances as if cruising. Leyendecker mapped the men’s gazes to circumvent their women companions, to point instead to men they resembled. When I noted how all the men looked alike, Christian explained they were facsimiles of the artist’s young lover, Charles Beach, who became the template for the Arrow Collar Man.

This man was in most of Leyendecker’s ads: for Arrow and Cluett, as men with golf clubs exchanging flirtatious glances; for Kuppenheimer, as two men eyeing a third, ignorant of a woman drawn as a literal siren; and for the Marines, as a pair of them on a cliff, eyeing a ship on the horizon, one on his stomach, ass up, with the other standing behind him, waving a flag positioned as if he himself were at full mast.

As a gay Filipino immigrant kid, Western culture gave me no reflections, no confirmations of my lived reality, only aspirations to whiteness.

I loved Leyendecker’s style. His distinctive brushstrokes in oil and turpentine complemented the strong lines in his art, from the pleats and creases in clothing, to the jaws and cheeks of men who mirrored Christian, debonair. I identified with them as much as a passion for suits and Ivy League drag would let me. But I didn’t see myself in this art, in these homosocial worlds. In fact, growing up, I didn’t see anyone like me in American popular culture at all.

Though I could project myself onto Carrie in Sex and the City or Will from Will & Grace, the fact remained: They were white. I was not. With Will, at least, there was a smidge of identification in that we were both gay men. When it came to Asian representation on screen, I saw characters and bodies with which I shared only a partial resemblance. There was Lucy Liu in Charlie’s Angels, Jackie Chan in Rush Hour, Thuy Trang as Trini the Yellow Ranger in Power Rangers. They were all Asian, yes, and powerful ones at that. But none of them were Filipino. Or gay. Or gay and Filipino.

Even in private, my imagination was limited by what I saw in pop culture. When I wrote a very bad novelization of my first year at Vassar, I cast Darren Criss, a mixed-race American actor, as myself. Though Darren is Filipino (his mother is from Cebu), he’s white-passing; his break-through out-and-proud gay character on Glee was portrayed as white. As much as I admired what Darren represented, I didn’t feel like he represented me. By that same token, I envied his ability to pass in America. In casting him as me in my book, I wished for the same privilege of passing, even if only in art.

I’d done the same when I first started exploring who I could be on the internet. I concocted a whole other persona, a white boy I named Jonathan. My profile picture was a portrait I’d stolen from someone’s blog. My internet friends were under the impression I was an out teen from Baltimore, with a doting boyfriend and accepting parents. In those days, we were told to be anonymous online. Protect your identity, never put your name in your email. So why not be someone else? There were so many more white images in America to choose from anyway, to pass off as my own. So the decision to pose as white was a matter of convenience. That was the lie I told myself.

In his essay “The Decay of Lying,” Oscar Wilde argues that life imitates art, not the other way around. “Literature always anticipates life,” he writes. “It does not copy it, but moulds it to its purpose.” Barthes might contest this thesis. He says in Mythologies that literature’s task is a delayed, rather than anticipatory, confirmation of the real. Either way, these white gays might agree that meanings are consciously grafted onto what we see in nature.

Wilde makes an example of London’s fog. People see it as a phenomenon with “mysterious loveliness,” he says, because that’s how poets and painters have rendered it in art. Of this mystique and romance ascribed to fog in a collective imagination, Wilde writes, “They did not exist till art had invented them.” That makes art, Barthes might say, the grand exercise in mythmaking. In this case, it’s fog as signifier, with a hazy and dreamy London as signified, to create a sign, a language, deployed by artists that their audiences, in turn, template onto life.

Whether by art or advertising, I was taught what to see and how to see it. Michelangelo’s David. Leyendecker’s Arrow Collar Man. Calvin Klein’s Marky Mark. I saw them as prescriptive, rather than descriptive, signs of beauty, of masculinity in the absolute. But I didn’t see myself in these images, nor in so many televised and canonized imaginations. As a gay Filipino immigrant kid, Western culture gave me no reflections, no confirmations of my lived reality, only aspirations to whiteness. My life then, I had decided, must imitate this art, however inaccessible. I learned to want what I could never be.

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Groom Will Keep His Name: And Other Vows I’ve Made About Race, Resistance, and Romance by Matt Ortile. Copyright © 2020. Available from Bold Type Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.