The late illustrator Maurice Sendak would have turned 92 today, and I imagine he’d have had the same contagious attraction to childhood wonder that made him such a compelling storyteller.

Well before his success with projects like Where the Wild Things Are, the Little Bear books (let’s not sleep on how good that TV show was), Outside Over There, and other works, Sendak had other aspirations: for a time, he and his older brother, Jack, were serious about becoming artisanal toy-makers.

There’s nothing like prolonged childhood bed rest to get a kid to fixate on something, and that’s what happened in Sendak’s case. In a 1966 New Yorker feature, Sendak told the author about the first books he’d ever received, from his sister: The Prince and the Pauper and The Three Musketeers. So much did Sendak love the books as objects in their own that he refrained from actually reading them for a while.

“It felt so good just having them,” he said. “They seemed alive to me, and so did many other inanimate objects I was fond of. All children have these intense feelings about certain dolls or other toys.”

At the time, many of Sendak’s own childhood toys were still at his parents’ house, and whenever he visited them, he also “visited” his toys (I hope that was code for sat open-legged on the carpet and talked to chunks of wood). Sendak was exploring the very Sendakian themes of loneliness and attachment in his early work Kenny’s Window (1956), whose protagonists occasionally chats with some of his favorite toys, including a stuffed bear and a lead soldier.

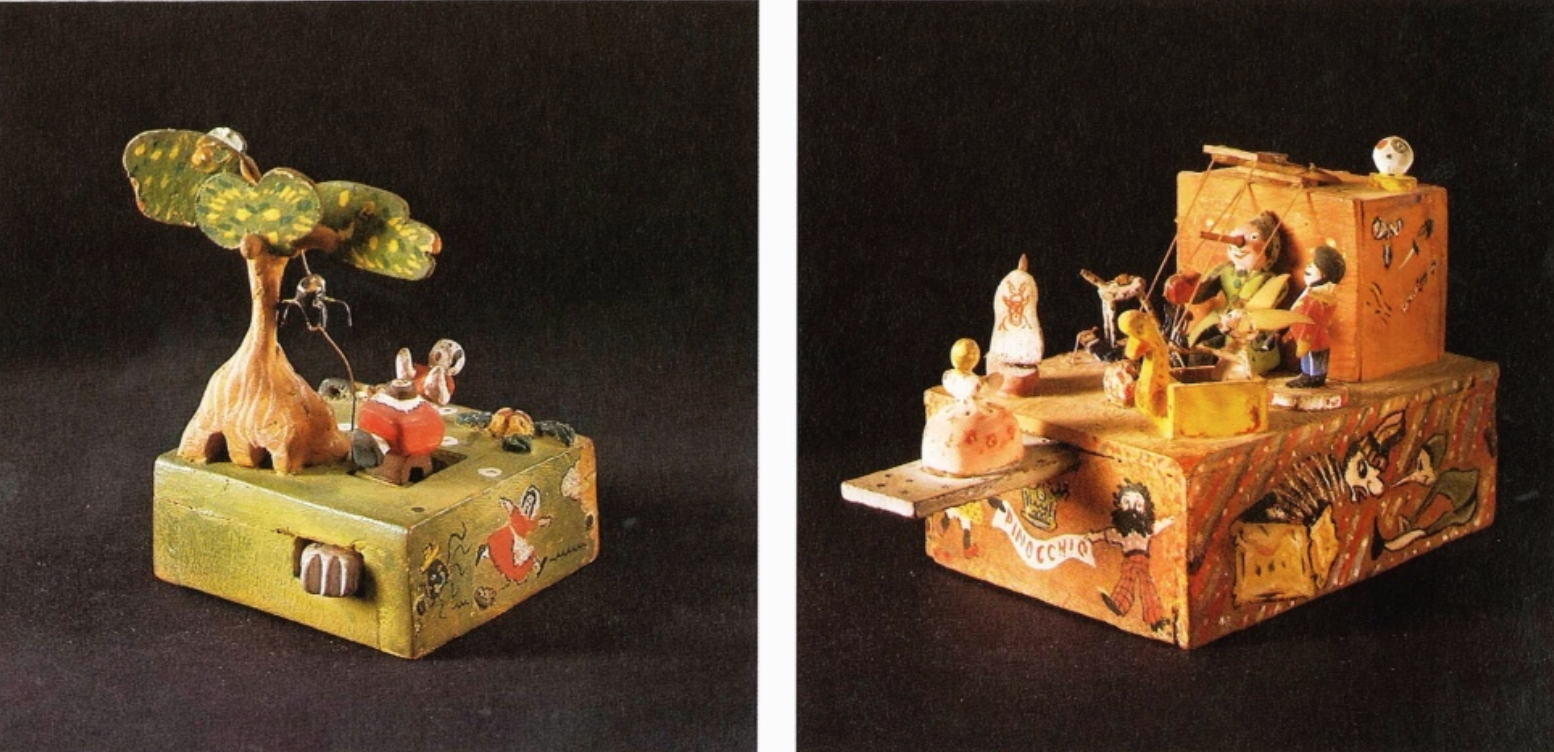

Once he graduated from high school in 1946, Sendak worked at a window-display house in lower Manhattan, helping create store window models of figures like Snow White and the dwarves using chicken wire, papier-mâché, plaster, and paint. He left after a couple of years and started working with Jack, one of his favorite collaborators, on moving wooden toys that performed scenes from fairy tales like “Little Red Riding Hood” and “Hansel and Gretel.”

Feeling bold, the Brothers Sendak took their German-style, lever-operated creations to FAO Schwarz, the legendary toy company, where they were told that the work was good but would be too costly to mass produce.

“We wanted a workshop of little old men creating the little wooden parts,” Sendak told The New Yorker, “and we would not have permitted any kind of plastic substitute.”

Richard Nell, Schwarz’s window-display director, was impressed and invited Sendak to assist in window display-making. Sendak worked at the company for three years while taking night classes in drawing, composition, and oil painting.

Thank goodness he did!