In the second half of May of 1940, my grandfather Gaston Messud, a 34-year-old French Naval officer reporting to the Deuxième Bureau in Paris from Salonica on the movements of the Italians, all too aware of their imminent entry into the war on the Axis side (this occurred on June 10), and anxious, too, about the fate of his beloved France—Paris would fall, of course, on June 14—dispatched his wife, my grandmother Lucienne, her invalid sister Jeanne and their two children—my father, François Michel, then almost nine, and my aunt, Denise, aged six—to return by train across Greece, Italy, and France to Marseille, and thence by boat to their permanent home in Algiers (the capital of the French colony of Algeria). Haste was of the essence, because once Italy entered the war it would close its border with France, and safe passage would no longer be possible. They did not know when—nor perhaps if—they would see one another again.

On May 22, Gaston writes to Lucienne from Salonica (now Thessaloniki), the ancient cosmopolitan city on the Aegean in Macedonian Greece where they’d been living for eight months in a lovely villa with a large garden at 175 Rue Reine Olga: “You must be, just now, all going well, somewhere not far from Milan… Today I hope that Italy will remain a good 24 hours longer at peace so that you have the time to pass through…” His letter, addressed to the Select Hotel in Marseille, was forwarded to cousins in Algiers, and thence to the rural village of L’Arba, to the home of his great aunt Tata Baudry, where my grandmother would eventually receive it.

On the 29th, he writes again: “I worry that you won’t have found in Algeria the calm atmosphere that I would have wished. You, be calm, be courageous, be joyful. It’s necessary for yourself; it’s necessary for the children; it’s necessary to set an example.” More than that, he writes: “Michel must work hard. I want him to enter 6e [the equivalent of sixth grade] in October. Remind him that he promised me always to think of France… Love the children, imagine that they are ‘us.’ Gently, and in such a way that they can understand, speak to them of honor. How painful it is to think that the world might crumble.”

On May 24, from Marseille, Lucienne writes to Gaston—a letter that arrives in Salonica on the 31: the post still worked well. “I made a long journey, tiring, which could have been wonderful with you and without the war. It is beautiful, beautiful enough to make you weep, this month of May, above all when one thinks of the killings, the massacres, the devastations that the countries that I crossed may be subjected to, the way others—equally beautiful, equally rich—have already been. I wish I could tell you all that I saw, heard. I will tell you nothing. The journey was rough: the news that reached us was crazy-making. From the mouth of someone reading the newspaper, it raced along the train corridors and blew hot in our faces. Triumphant [Fascist] headlines. I resisted, and I even said to a devastated Greek man from London that we had to wait to be in France to know what was true. Crossing an Italy that you could feel was preparing for the adventure of war, an Italy at the same time in full patriarchal activity: the harvesting of the hay, fields worked like gardens. Milan! No change. French and English money are no longer accepted.”

“Love the children, imagine that they are ‘us.’ Gently, and in such a way that they can understand, speak to them of honor. How painful it is to think that the world might crumble.”

At the Milan station, the man at the ticket counter directed Lucienne to board the wrong train. He told her that the train she was looking for hadn’t been running for three days. Two porters took her aside and guided her to the correct quay, helped her board the right train—this middle-aged woman (thirteen years older than my grandfather, she was then in her mid-forties) with her invalid elder sister and her two small children, loaded down with suitcases—even as they knew she could not give them any money because she was unable to change her currency into lire.

On the journey, Lucienne suffered migraines so strong they made her cry. “Here we are separated, for how long?” she wrote to Gaston in her next letter. “May God protect us. I saw Notre Dame de la Garde [the Catholic basilica of Marseille] from afar and I promised that we will climb up to the church all together after the war, when we will be together, the way we climbed there together when we left France… I need courage, not to think of myself but of the little ones, to watch over them even more than before because I am alone with them. I love you; it seems to me I haven’t said it often enough.”

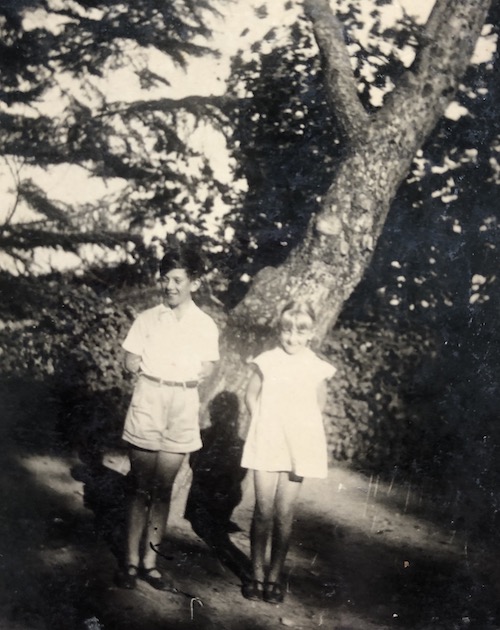

The author’s father and aunt, Istanbul, 1941.

The author’s father and aunt, Istanbul, 1941.

By June 3, the situation was worsening. Gaston wrote to Lucienne, still from Salonica: “Marseille was bombed yesterday. I haven’t yet had any details, because it’s Monday and I must wait for the Independent [a local newspaper]. H is staying; P is summoned back to France. I am disgusted to see the spinelessness and defeatism crowned, and myself disavowed… I am bored. I don’t rightly grasp my state of mind. I don’t understand how I am living… It will be two weeks tomorrow since you left, and I am living without the slightest idea of the day when we will see one another. Perhaps in six weeks, perhaps in six months, perhaps in two or three years… Life is strange; each time I find myself alone, and above all in the morning when I waken and become again aware of my solitude, I ask myself what we are doing on this earth. In one sense it’s totally natural: my reasons for living are far away. I note with fatigue that a new day begins… This empty house saps me of all will, but I think a room at the hotel would be more annihilating still. I am not sad. I am in a waiting room. Leaving here, where will I go?”

On June 6, Lucienne wrote, from Algiers: “How far away from you I feel. Salonica seemed to us the end of the earth; it is. I have the impression that I’ve left one world to regain another. Our worries from over there are foreign here. Here, everyone thinks above all of the war in France, and nobody is remotely concerned about the distant Middle East. I think of it always.” She gives news of Gaston’s family, and of her own. “My soul, my life, may God protect us,” she writes, “And may He spare us, and may He conserve our marvelous love, its dignity, and may our children live happily alongside us, and retain a tender memory of our family life. May they learn, watching us live, that home is the refuge, that it is intangible, and that nothing can shake or destroy it… We must inculcate in the children respect for sacred and divine things: for the homeland (“La Patrie”), for family; we must give them a sense of duty; we must make of them a man and a woman who are honest and courageous, conscious of their responsibility, courageous in accepting and carrying out the tasks they undertake… For us, for them, we must continue the masterpiece of our life and love one another, love one another with all our strength. Our life must be an example to them, a comfort, and we must give them a profound desire to follow in our footsteps.”

On the same day, Gaston wrote from Salonica—a letter that was carried by diplomatic pouch to Paris, and sent on from the Rue Cler, in the 7e, on June 10—just days before the city was occupied. “We can’t be knocked out, in this war; we could only lose by abandoning the fight. We absolutely must not abandon it. Napoleon went as far as Moscow, as far as Madrid, and he didn’t vanquish either Russia or Spain. Even if he arrives in Paris—may God spare us that horror—Hitler will not have vanquished France. And the grave-robbers in Rome are mistaken if they imagine they’ll be able to pillage our tomb, because we will not fall.

“Our France, our poor and beautiful France. I am suffering as you are suffering; I am afraid, but I have confidence.”

“Jaguar, Chacal, Adroit, Foudroyant, Ouragan and three-times-victorious Sirocco. And you too, obscure Niger. [These French boats were sunk in the battle of Dunkirk.] On all of them I had at least once set foot. The Jaguar was the Admiral’s, the Foudroyant was my chief of division when I was on the Brestois. They are at the bottom of the ocean. May God have the souls of their ships—that’s to say, may He ensure that their memory endures, and that other ships, to come, will carry their names the way our sons will carry ours. It is difficult not to be infinitely sad, and it’s difficult, in spite of the teachings of Christ, not to feel hatred rising inside, higher each day, drowning out all other emotions. We will never, never be cruel enough…”

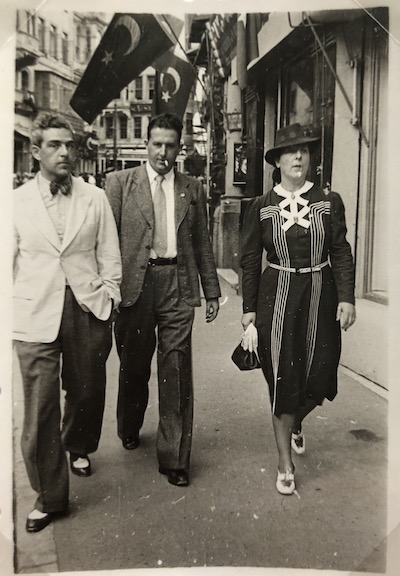

The author’s grandfather (left), and grandmother, Istanbul, 1941.

The author’s grandfather (left), and grandmother, Istanbul, 1941.

Later in the same letter, he writes: “Love our children; protect them. Don’t let them see what is ugly on this earth; they will see it soon enough. When they are with you, be joyful; assure them, against all those who would wish them to believe the contrary, that happiness exists, and that while doubtless luck plays a big part in the search for it, so too does will. That happiness is fought for, and protected, that it is a continual construction that requires faith. Think, my darling, that without faith we would perhaps have listened to those who told us that we were crazy to get married. Whatever happens now, we must thank God; he has already given us a magnificent run. I love you, Aïni[1]. You are all life. This isn’t merely a word: you are all my life.”

In subsequent letters leading up to the French surrender, Gaston importunes St. Michel and Ste. Jeanne d’Arc to save France. His inability to countenance defeat becomes more desperate with each passing day. By June 18, he writes: “France seems lost, but our Navy? What will our Navy do? I think we will fight, and that the Navy, in any case, can serve in the conversations that are underway. If they want the Navy to stop fighting, they must grant France honorable conditions. If there aren’t such conditions, the Navy will continue our task, alongside the British fleet, and the Navy will save France. France and her Empire. As dark as this day may be, I absolutely refuse to despair. I have confidence—When I will finally be on a ship, don’t be worried, my soul, nor sad. Think that I am happy. Consider: there can be no happiness for us if France must die, neither for us nor for our children. In spite of all the horrors of this war, there will be joy in life if eventually our cause triumphs… Pray God, my soul, that when the day comes, I will have the physical courage to accomplish with dignity what I must, what I want to accomplish… Let us thank God for having been good and merciful to us… And may His will be done. His will cannot be to kill the eldest daughter of the Church.”

“Even if he arrives in Paris—may God spare us that horror—Hitler will not have vanquished France.”

Meanwhile, Lucienne attempted to find a place to live with the children. There was nothing available to rent in Algiers, and in any event schools were suspended and children were being evacuated to the countryside. She took François-Michel and Denise, along with another aunt, Tata Titine, to stay with the aged Tata Baudry in her flat in the village of L’Arba, 30 kilometers outside the city. There, dismayed by the grim disorder and dirtiness of the tiny two-room apartment that was crammed with a lifetime’s possessions, Lucienne wrote to Gaston on June 16 (a letter that reached him eventually in Beirut in August, having traveled first to Salonica, then to Athens, then on to Lebanon): “I am trying to write to you. It is wartime, and we are homeless. What is most painful to me is the lack of solitude… I have stayed in L’Arba: they are evacuating the children from Algiers (here there are 400 housed in the schools). Classes are interrupted. I am worried for our children; that’s why I’m here, without hope of anything better. Everything has been rented, even the Arab houses; we are camping. We are afraid. There are bombing alerts in Algiers, and here… we have dug a trench in the garden. Our France, our poor and beautiful France. I am suffering as you are suffering; I am afraid, but I have confidence. In my heart, I am certain that She cannot die.”

Lucienne asks, in a letter of June 17, “Will we ever regain our youthfulness of spirit?” Years later, in 1975, my grandfather wrote: “The answer was in the negative. The shock of June, 1940, followed by so many months of tribulation, dealt a decisive blow to our youth. I didn’t recall that she had posed the question, but I always had the impression, after the fact, that I watched myself live, or that I watched us live, that I passed brutally, in those last days in Salonica, from being a young man to being a mature man. Certainly, we did retrieve our joyfulness, we learned to sing again—me always off-key—but it was never the insouciant joy of before the defeat. What a defeat it was.”

[1] Aïni in Arabic means ‘spring’ or ‘source’: it was my grandparents’ pet name for each other.

—————————————————

The preceding is from the Freeman’s channel at Literary Hub, which features excerpts from the print editions of Freeman’s, along with supplementary writing from contributors past, present and future. The latest issue of Freeman’s, a special edition gathered around the theme of power, featuring work by Margaret Atwood, Elif Shafak, Eula Biss, Aleksandar Hemon and Aminatta Forna, among others, is available now.