One night recently I was talking online with my friend Peter, a GP in Edinburgh where we both live, about how he had found working during the pandemic. Peter loves poetry (he even teaches his medical students by giving them poems) and his thoughts had been running in this direction. In particular, it was metaphors—military metaphors of “frontline” NHS staff “battling” an “invisible enemy”—that were bothering him.

“People in the NHS are just doing their best, in difficult circumstances,” he said. “We need new metaphors that empower people to make good decisions in a crisis.”

Peter had spent much of the previous week talking with his most elderly patients about what they would want to happen if they became so unwell they needed to be placed on a ventilator. Once intubated, some would never be able to breathe unaided again. “These are such important conversations,” he said, “and a privilege to be part of. Military language just doesn’t help at all.”

In Illness as Metaphor, Susan Sontag argued that illness and metaphor have a long and dubious common history. Many 19th-century diseases were seen as expressions of defective character or even, going back to the classical world, supernatural judgement. Even today, making disease symbolic has caused misunderstanding and pain, separating the unwell from proper treatment and encouraging the complacent. For weeks, Donald Trump spoke of the “Chinese virus” as if it were a familiar threat, obscuring the fact that Covid-19 was spreading between Americans who had not traveled abroad. Writing in The New Yorker as the US went into lockdown, Paul Elie lamented that, “enthralled with virus as metaphor and the terms associated with it—spread, growth, reach, connectedness—we ceased to be vigilant.” Harking back to past military victories on VE Day led many in Britain to swap lockdown for street parties, as if willing the virus to resemble an enemy they could recognize and defeat.

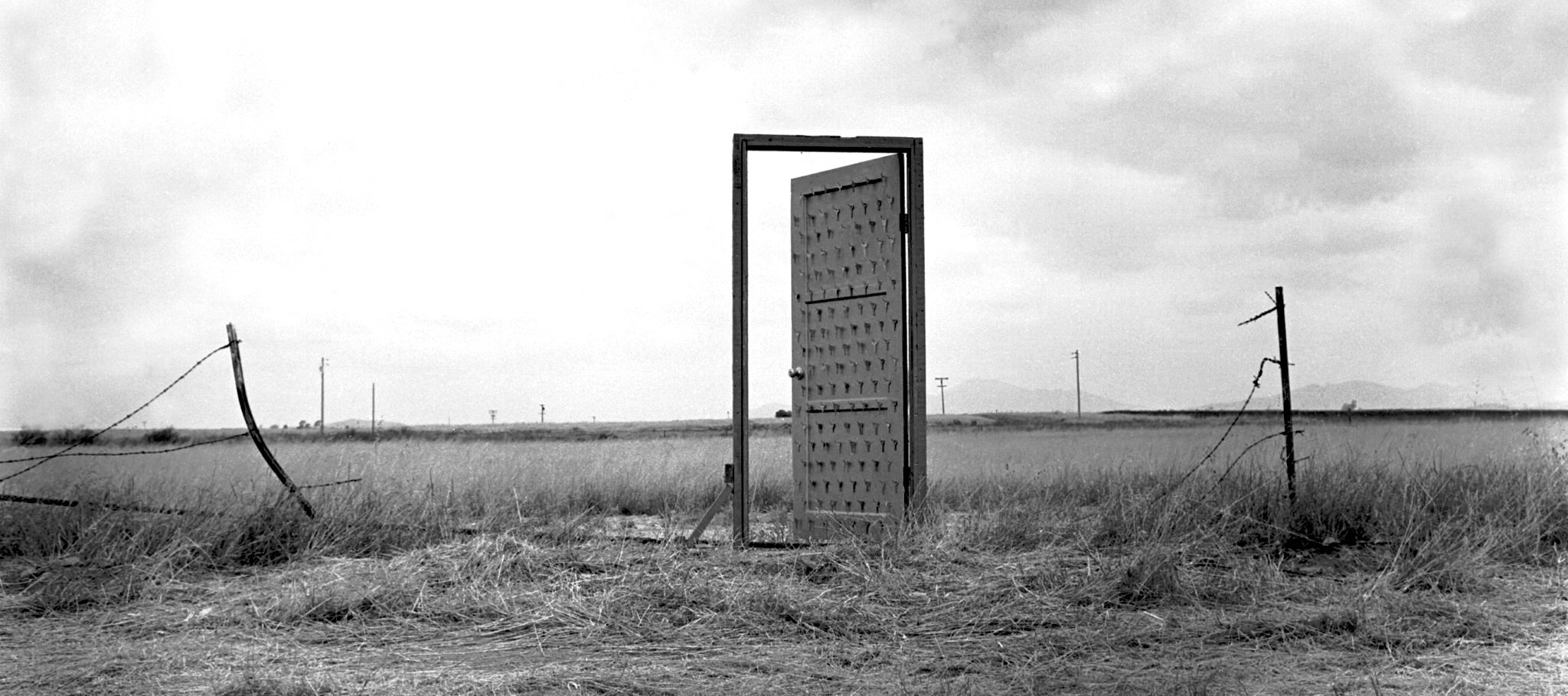

So it might seem that my friend was skirting some dangerous ground in suggesting that we need new metaphors. “The healthiest way of being ill,” Sontag advised, “is one most purified of, most resistant to, metaphoric thinking.” But this underestimates the role metaphor plays in helping us make sense of a world that has fundamentally shifted around us. The term’s origin is in the Greek expression to be carried across. Metaphors make meaning by substituting one term for another. Since the pandemic arrived we have all found ourselves carried across into a new reality, the world we knew replaced by one that resembles it but is also radically changed.

Since my family decided to isolate we have lived simultaneously in the kingdom of the sick and the well.

Seven days before the whole UK entered lockdown, my family decided to self-isolate. None of us are in a high risk category, but my wife had a developed a cough and it seemed right to assume the virus was circulating in our household. It remained ambiguous: her symptoms progressed to include breathlessness, exhaustion, and loss of taste and smell, but no fever; none of the rest of us had any symptoms at all. She recovered, but was easily made short of breath for weeks afterwards. Had she had it, or not? Were the rest of us somehow unaffected or just asymptomatic?

Sontag wrote that “everyone who is born holds dual citizenship, in the kingdom of the well and the kingdom of the sick.” But the nature of this virus, which does not produce symptoms until several days after infection and infects some without any outward sign at all, means most of us don’t know which territory we inhabit. In the absence of the most severe symptoms or a reliable test result, the prospect of contracting or transmitting Covid-19 continually moves us between opposed realities.

Since my family decided to isolate we have lived simultaneously in the kingdom of the sick and the well. The terms of our dual citizenship mean that, to be a good citizen of both, we must imagine ourselves already ill. While my wife was sick I was hyper-vigilant about any tickle in my throat or cough from my children, continually interpreting any symptom in light of its similarity to the symptoms. Since she has recovered we persist in a state of contradiction, as if another reality exists behind the one we’re living. We cannot afford to read ourselves literally, when every touch of hand to face feels loaded with potential consequences. A kind of metaphorical being takes over instead: we must continue to act as if we have the virus, regardless of how we feel.

In her essay “On Being Ill,” Virginia Woolf writes that the world is altered for the unwell person: “how the world has changed its shape; the tools of business grown remote; the sounds of festival … heard across far fields.” But what was once the province of the sick has become one we all inhabit. Streets and buildings are empty, the sky is sparse of traffic. The shape of our days has changed. We’re at home, in the most familiar surroundings, but a new life has been substituted for the old.

At some point the lockdown will lift, and will find ourselves carried across, again, into a world that resembles the one we knew but is also fundamentally changed.

Illness, Woolf says, discloses “undiscovered countries.” The undiscovered country of my self-isolation has been no less rich for being ordinary and commonplace. It has involved struggles and quarrels, but we have learned to inhabit new rhythms. I have watched with gratitude as my children have adapted to sudden change. There has been grief too, for life as it was, and a lost opportunity to grieve the dead, as I was unable to attend my grandma’s funeral. Still, together we have been remaking our days from a more limited store of materials.

Slowly, we have become accustomed to the constraints of lockdown. But at some point the lockdown will lift, and will find ourselves carried across, again, into a world that resembles the one we knew but is also fundamentally changed. Already, some countries are beginning to move out of lockdown, in others the resolve is beginning to fray; yet a vaccine, we’re told, could be years away. Public life will probably resume only fitfully, as we move in and out of periods of isolation. To negotiate this, we could do worse than reflect on metaphor, and its strange sense of being carried between worlds.

Woolf thought that illness turns us inwards, separating us from “common needs and fears.” But common needs and fears fix us together now more than any time in living memory. In bringing seemingly unlike things together, metaphor sponsors a sense of things in common. Understanding ourselves as possibly ill—carried between the kingdoms of the sick and well—allows us to go beyond what we know and enter the experiences of others. The ability to do this will be vital to life in the uncertain times to come, to avoid another deadly peak, and if the post-pandemic world is not to repeat the mistakes of the one it replaces.

Perhaps, despite Sontag, metaphor can be a healthy way to approach the pandemic and what comes after. In a recent article for the Financial Times, Arundhati Roy railed, as my friend Peter had done, against world leaders who reach for metaphors of war in times of crisis. The pandemic is “a portal,” she wrote, “a gateway between one world and the next.” The choice, she says, will be between a world we know and one we have yet to imagine. Metaphor is a challenge to our imaginations. It asks us to let go of how we have learned to think of something and accept a fresh way of seeing. Every metaphor offers us a choice: we may focus on what brings its two parts together, or on what keeps them apart. Embracing the possibilities we find in metaphor can help us step across from the old world into the better one we hope for.